Baseball Hall of Famer Leo Durocher once said, “Nice guys finish last.” Leo obviously never met Chuck Nicklin.

The first time I met Chuck, I was presenting a slide show on the Red Sea to a tough audience from the San Diego Underwater Photographic Society. At the time, they were putting on the most prestigious underwater film festival on the west coast. For two days every year they filled the giant civic opera house for their shows. I was a carpetbagger from Orange County trying to get my slideshow accepted in the show, and felt about as welcome as Bill Clinton at the Fox News studios. When I finished the presentation, I looked at the frowning faces of the judges.

But Chuck walked up to me and said, “Congratulations. That was the best show we’ve seen here in a long time.” I was blown away that Chuck Nicklin, world renowned photographer, cinematographer, and diving pioneer, would make the effort to encourage a nobody like me.

Chuck has encouraged a lot of nobodies who later became somebodies . Some of today’s leading underwater shooters, including Howard Hall, Marty Snyderman, and his son, Flip, got their start working for Chuck at the Diving Locker. Unlike photographers who feel threatened by newcomers, Chuck is secure in his own ability to keep raising the bar. And he’s still raising that bar as he approaches his 80th birthday (September 2007).

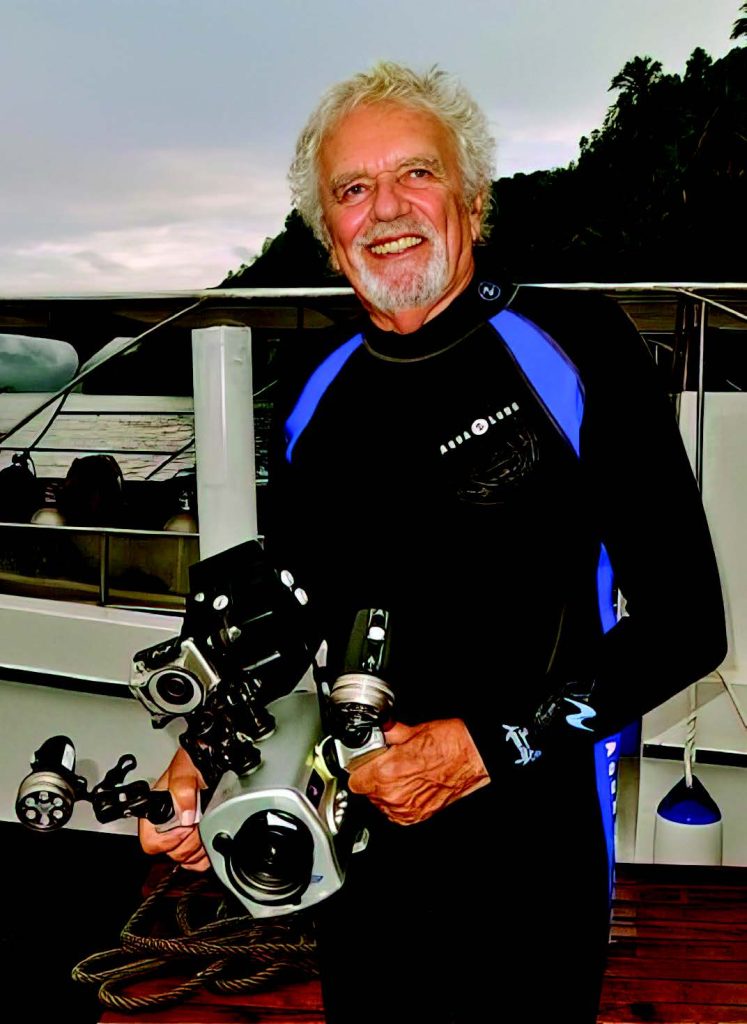

Most divers of the pioneer era have hung up their fins or moved on to the great coral reef in the sky. Chuck is still at the top of his game, traveling the world and capturing the action in high definition video, and leading trips to exotic locations with his wife, Roz. He has been an underwater shooter for nearly 60 years, ranging from stills in National Geographic to Hollywood movies, television, and Imax films. Beginning as a breath-hold spearfisherman before the introduction of scuba, Chuck opened one of the west coast’s first dive shops, the San Diego Diving Locker. He learned from some of the early legends: Jim Stewart, Connie Limbaugh, and Ron Church; then helped the next generation get started.

During the years he owned the Diving Locker, it became a Mecca for traveling diving dignitaries coming through San Diego. Marty Snyderman recalls, “I don’t know if it was design or by good luck. But there wasn’t another store anywhere in the world that I’m aware of that had that kind of body of energy about photography at that time. Chuck was certainly the leader of all that.”

Mary Lynn Price, a rising star in underwater video, is another shooter who credits Nicklin with getting her started. In 1995 she went with his group on her first foreign dive trip, to the Bahamas. In the middle of a shark feed, Chuck handed her his Hi-8 video camera and signaled her to start shooting.

“Chuck has been my underwater mentor ever since,” she said. Mary Lynn, in turn, has been his mentor in editing on computers. “He made the transition to the computer age before many of us did, and is one of the most computer comfortable people I’ve met,” she concluded.

Nicklin is constantly on the move to exotic places, organizing and running trips. He keeps threatening to retire, but several friends have been on “Chuck’s last trip” four or five times.

His medium of choice today is high definition video, and he hasn’t lost that magic touch. The hardest thing in underwater video is shooting macro subjects without camera movement. Nicklin is a master at that, despite never using a tripod. He’s still setting the standard for people half his age.

Eric Hanauer: How did you get interested in diving?

Chuck Nicklin: When I first moved here from Massachusetts, I’d look down the cliffs at the ocean and thought that’s really neat.

After I got out of the Navy, I went down to La Jolla Cove one day because I just had this urge for the beach. There was a kid in the water with a diving mask. I asked his father, “What is that?” He asked if I wanted to borrow it. So I used this little kid’s mask, one of those round, hard ones by Sea Dive. I looked around and said, “This is for me.”

A relative in the Navy bought me a pair of black Owen Churchill UDT fins. My Sea Dive mask came from a local sporting goods store; its hard rubber edge had to be sanded to make a seal. An old Navy sweater kept me from freezing on free dives for lobsters and abalone.

EH: Do you remember your first scuba dive?

Nicklin: The first time I ever went underwater and breathed off anything, it was a gas mask and a little bottle of oxygen…I went to Mission Bay with my father and he put a rope on me. I said, “If you see me stop moving around, pull me in.” I turned this thing on to take a breath, held it, turned it off. This was repeated for every breath… for maybe five minutes. I thought there’s got to be a better way.

I was in the small grocery business, too poor to buy one of these fancy Aqualungs…The first day of abalone season, it was a tradition to go to Bird Rock in our wool sweaters. I scammed a short Pirelli dry suit, with a band around the waist. Over the top of that I would wear a long john top and bottom. It looked weird, but was necessary to protect the suit. I spent all my free time talking diving. In the back room of the grocery store, I had pictures of diving on the wall, I had scrapbooks, and was gung ho for diving.

EH: When did you start on the Aqualung?

Nicklin: In 1953. I had a friend, Bob Casebolt, who was working at Convair. They had a recreational dive club, Delta Divers, and a half dozen tanks. Bob wanted to learn how to dive and so did I. So I joined the club even though I didn’t work at Convair. My instructor was George Zorilla. He was an Olympic swimmer out of Argentina, was in the swimming business for a long time, and taught my sons, Flip and Terry, how to swim. All the course consisted of was talking about it for a while, putting on those little beanie 38-cubic-foot tanks, a double-hose regulator, and making a dive at the shores. I didn’t really get a C card till I started the Diving Locker and took a quick course through the city of San Diego to be an instructor.

We did some weird things, makes we wonder how we got through it. I remember being on the bottom with a bag of ten abalone, the legal limit in those days…I was starting to breathe hard, kicking away and starting up, and all of a sudden my feet hit the bottom. I hadn’t moved at all…was scared to death and dropped the abalone. I couldn’t drop the weight belt; it was a cartridge belt with lead in the pockets.

We used to dive in the north canyon and shoot rockfish at about 140 feet, deep enough so their eyes would pop. We knew we should be decompressing, but weren’t quite sure how the whole thing worked. So we would take little 38s and lie down at the bottom of the pool at Buena Vista Gardens, thinking we were decompressing. This was probably 45 minutes after we got out of the water.

I was a hunter in the early days. The last black sea bass I speared weighed 376 pounds. They would dive down and wrap themselves in the kelp; you’re free diving 60, 80 feet to cut them out. Get that line wrapped around you, you’re in a lot of trouble. I did all that and feel sorry about it now.

For ten years I spent any free time at the ocean, free diving and spear fishing. And that’s how I met Connie Limbaugh (diving officer at Scripps) and Jim Stewart (Limbaugh’s successor) and all those guys, through free diving.

EH: Do you remember how you met Connie?

Nicklin: A friend of mine, Homer Rydell, was a salesman for Gallo wine, and he invited me to his house to meet Connie, and we went lobster diving at the cove before it was a preserve. Later we went on an overnight Baja trip together along with Elizabeth Taylor’s brother, Howard, and over time became close friends.

Limbaugh, Stewart, Andreas Rechnitzer, and Wheeler North (researchers from Scripps Institution of Oceanography) were partners in a part-time consulting business, doing their research out of the back room of what would become the Diving Locker. In 1959, a contract on testing the offshore sewage outfall brought in enough money to expand the business into a dive shop. The problem was that they all were graduate students, and had neither the time nor the retailing expertise to run the shop. Rydell recommended me. I was in a small business, knew when the checks would clear and all that stuff; that’s good training for running a dive shop. They had a choice of me or Ron Church…and decided I would be the manager, and Ron would work with me.

The Diving Locker opened on June 15, 1959. I’ll remember the date forever. June 14, 1959, was the only authenticated shark attack off San Diego, the day before we opened. Business was really slow. Our entire budget of $5,000 was spent on a Rix compressor. But because of Limbaugh’s reputation and his connection with Rene Bussoz (Aqualung), the manufacturers stocked us on credit.

Jimmy (Stewart) and Andy (Rechnitzer) and those guys did more than just help running the store. Their reputation made our store a sort of scientific headquarters. Anyone in San Diego on a scientific mission went to the Diving Locker, and that helped us get started. Many a day we had a lot of empty boxes on display… because we just didn’t have the capital we needed. When Bev Morgan was closing his surf shop, he came down and taught me how to make wet suits. I was a one-man show for a while, made my first suit on the floor of my house.. I would sell them the suit, cut it, glue it, try it on them, and take their money.

During our first class, Jacques Cousteau was in town. The class was in the back room, and we introduced him. He said, “This is your introduction to the ocean, I hope it’s as good for you as it is for me.” Every once in a while someone from that class staggers through the door and asks, “Do you remember when Cousteau welcomed us to the ocean?”

EH: What was it like to run a retail dive shop in those days?

Nicklin: The main reason for diving was to gather. Abalone, halibut, and all that. That was the basis of our business. The main lines in those days were US Divers, Swimaster with Duck Feet fins, Waterlung, the first serious single hose regulator, and Voit was in it then. Mike Nelson used to use Voit.

In those days we had a sort of crane-like device outside the store. When people shot big fish we’d take a picture and the newspaper was just eager to have that kind of stuff. Rollo Williams was the outdoor editor of the San Diego newspaper, and we’d talk to him a couple times a week about the water temperature, the halibut are in, that kind of stuff. There’s always word of mouth but in those days there were so few divers, the ones that were there got lots of attention.

EH: How big did you guys become? How many stores did you have?

Nicklin: At one time we had four. We bought out Dick Long’s retail business and ran that for a while. We didn’t make a lot of money but we had a lot of fun; there were a lot of things going on.

EH: When were you at your peak?

Nicklin: Probably in the mid 70s.

EH: What happened?

Nicklin: The biggest thing that happened, Flip decided he wanted to be a photographer. And Terry was sort of interested, and I was gone all the time. We had some poor management. I think the reason the Diving Locker finally was sold is that I didn’t want to do it any more, and Terry didn’t want to do it any more.

It’s tough on guys now that want to be in the business. Werner Kurn (Ocean Enterprises owner) is complaining about the internet. He told me about five people that came in, a family. Looked at all the suits, tried the fins on, checked out the regulators, were there for three hours talking to his employees. When Werner asked, “Can we start to write this up?” the guy said, “We’re going to buy it on the internet.” What happens is that guys in business these days stock the equipment, set up a location, hire the employees, and don’t get to make the sale.

Service and classes and travel are going to be a bigger part of the business as sales go south.

One of the things they have to do is make people realize diving is fun. It was so stupid, and I talked about it many times, not to take classes that had their lectures and pool sessions in San Diego, and then take them to someplace warm. Those people will stay in diving. To take people, especially those who are older and have a little money, and put them in that restrictive wet suit and throw them in that dirty water and in the surf, that doesn’t make customers. Then you’ve got to make it a little jazzy for the kids. They want something extreme.

EH: What’s your opinion of the tech movement?

Nicklin: I think there’s a place for it. It’s not enough to make the sport grow. I had four friends who were good tech divers but they didn’t make it.

One of the things that makes it tough on the diving business is that equipment lasts too long. If you’re in the camera business, you got to get your shoes on because it’s changing so fast. There’s not a lot of reason to buy stuff. Things don’t change much.

EH: How did you get started in underwater photography?

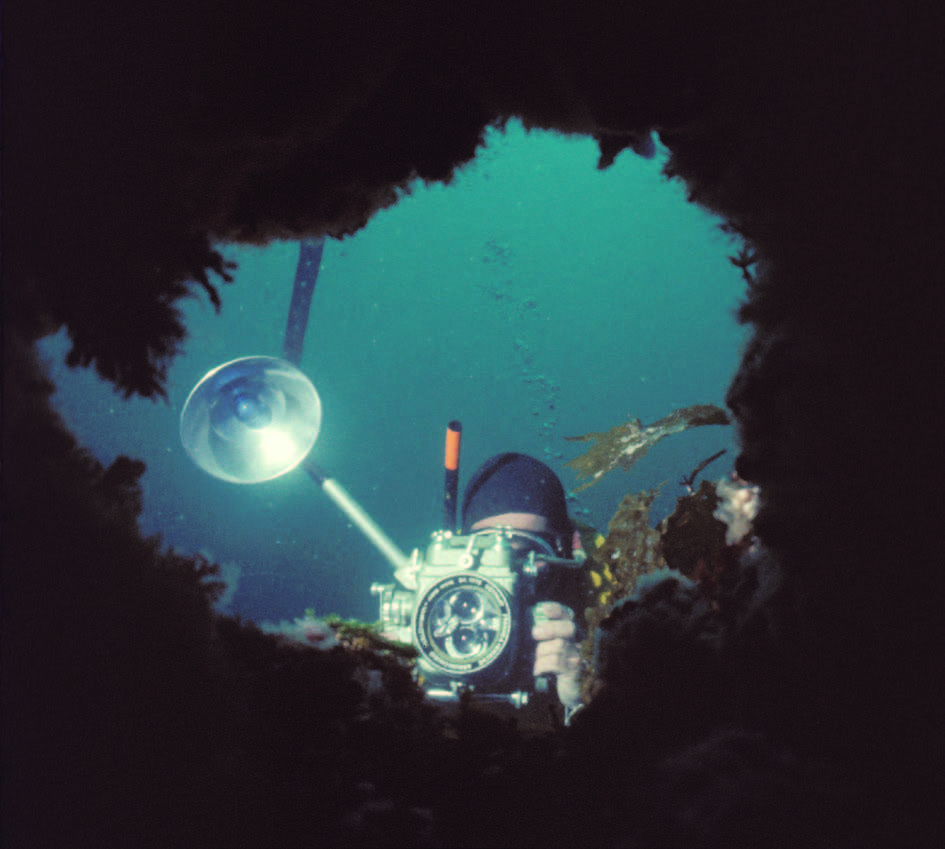

Nicklin: Connie and those guys picked Ron Church to run a film section at the store. Ron was the photographer for Convair; I think his early background was aerial photography. We used to go out with an old Rolleimarin with 12 exposures. He’d shoot while I looked for a subject, then I’d shoot while he’d look for a subject and we’d come in with six pictures apiece. Now you can go down and shoot 350 pictures if you want.

Ron and I got along pretty well. It was his idea to start Underwater Photographic Society (UPS). He built a darkroom in the back of the store. That was his aim, and my aim was to build a business out the Diving Locker name.

When Connie Limbaugh died in a diving accident, his wife, Nan, asked if I wanted his camera gear. So all of a sudden I had a fairly sophisticated 16mm camera and a Rolleimarin. I had a base. I had the wonderful friendship of guys like Wheeler and Jimmy that would steer photography to me. I had Ron to help me, and could get away, because after a couple of years there were other employees.

It was a big advantage to be able to get away…When a job came up, a lot of other fellows couldn’t do it because they worked five days a week. Convair would call with their submarine stuff and I would get involved …At first I was scraping money together to buy a roll of film, then it was, I just sold a picture so I can buy some more film.

EH: Your big break came on a whale shoot, didn’t it?

Nicklin: That’s right. One day in the early 60s, we were diving off La Jolla on Al Santmeyer’s boat, Duchess. Heading across the bay, we spotted a whale spouting. It was a Bryde’s whale caught in a net, the ropes digging into its flukes. It was weak from trying to breathe, and barely struggling. Bill De Court and I jumped in, dived to 20 feet and cut the whale loose, shooting pictures all the time. It was just one of these things that hit at the right time. Nobody knew anything about whales then. Our pictures were in the paper, in Time Magazine; people were calling from everywhere to interview us because we rode a whale. So this got a lot of publicity. I was getting a lot of calls, “You’re the guy who shot the whale, can you shoot this?” So the first thing you know, I was doing more of that kind of thing.

EH: What was your first movie assignment?

Nicklin: It was a Hollywood B film called Chubasco. The producer director was a friend of Wheeler’s and he suggested me.

They wanted shots of local tuna boats…at water level, in the net with the tuna and sharks. I said, ‘Yeah, I can do that.’ They said, ‘Bring diving gear. We’ll supply the camera; meet us at the boat in San Diego.’ So I got on the boat and they said, “Well, this is the camera.” I said, “Oh my God!” It was the first big Panavision 70mm, about the size of a steamer trunk. It weighed 300 pounds; they had to put it in the water with a crane. And I had been shooting 16mm. I had no idea what it was, or how to load it, and had never even seen a roll of 70mm film. They introduced me to my camera assistant. After the producer walked off, I asked him, “What do you know about this thing?” He said, “‘I know everything.” I said, “We are going to be a great team.” So all I had to do was take it in the water and point it.

At one point I was in the net with the camera, all sorts of skipjack screaming around. A stunt man was supposed to fall in and the other actor was going to jump in and save him. So I’m in the water, the guy falls in, sinks about two feet, and panics. He can’t swim. He wanted the job so badly and figured he would learn to swim when the time comes.

It was an easy time to be a photographer. Very few people were doing it. Red starfish pictures were a big deal

In the early days I did a lot of still photography. Ron Church, Chet Tussey, and I and some of the other early photographers started the Underwater Photographic Society. They used to have contests and a friend of mine, Ginny Kellogg, won with a picture of a red starfish. Even if it wasn’t in focus, it was a winner.

I did the first diving on the Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle built by Lockheed. Until they turned it over to the Navy, I did a lot of the photography. When they made their first deep dive, everybody got a dive on it and a plaque stating that they had ridden in it. On my plaque, they put “outside the DSRV” because I had always been on the outside to shoot it.

EH: How did you get started with National Geographic?

Nicklin: Bates Littlehales and I had became friends during a gray whale shoot in San Diego. He was assigned to go to Turkey and shoot George Bass’ expedition on a bronze age shipwreck. But he ruptured an eardrum on assignment in the Bahamas, and recommended me to take his place. They flew me back to Washington, said to throw away all my 2 1/4s, handed me a Calypso, a Seahawk housing with a Leica and a 20mm lens, and a couple of Edgerton strobes that hardly ever worked. For three days they gave me Nikons with black and white film, and I’d go off and shoot in Washington. They’d process that night, then tell me what they liked. They gave me the little booklet on how to shoot for Geographic: You need a sunset, you need a scenic with a little animal or a person, you need so many close-ups…a long list.

So I went off to Turkey and shot this story. We had a bell and a submersible decompression chamber. We swam into it at 20 feet, then they brought you up to 10 feet for the rest of your decompression. We also decompressed on a line. They had a bucket with books in it. As long as you kept the books wet they would hold together and you could read. We also did that on The Deep because we had such long decompression.

EH: You and Al Giddings have collaborated for many years. How did that begin?

Nicklin: I first met Al at the Pacific Coast spearfishing championships. Afterwards we were sitting around at Ron Church’s house and he says, “I’m going to Cozumel to shoot a film with the backing of US Divers.” I said, “That sounds like fun.” He said, “Come on along; we’ll shoot together.” I said, “I can’t. I’m in business, it’s hard to get away.” A short time later Al was down here showing his first film, The Painted Reefs of Honduras, at a film festival. When he was up on the stage he said, “You all know Chuck Nicklin, who owns Diving Locker. He’s going to shoot with me in Cozumel.” I told him, “I can’t do that, I’ve got no money.” A few days later he called and said, “This is your last chance.” So I talked to my wife, Gloria, and said, “I’d really like to do this.” And she said, “You only go around once.”

EH: That seems to be your motto now.

Nicklin: The once is getting shorter. (laughs)

EH: 16mm was expensive in those days.

Nicklin: That’s why not many people did it. Through Scripps I’d end up with extra film, donations. People knew I was interested in it and but primarily if you wanted to shoot 16mm you had to have someone who was willing to pay for it. It wasn’t like buying a one hour videotatpe. I just started doing commercial things and that gave me a chance to improve my skills and learn the business.

EH: What other kind of commercial things were you doing?

Nicklin: All kinds of stuff. I did a US Steel thing on Flip (a Scripps research ship that flips vertically to do ocean measurements.) I did a beer commercial for a Mexican company, did an Olympic commercial in a pool with synchronized swimmers. I did a lot of weird things. It was a very small group of people in those days, and what made it tough for new people was that the pioneers all helped each other. If Al had a job and didn’t have time to do it, he’d call me. If I couldn’t do it I’d call Jack McKenney. It was a good old boys’ network. Al and Jack were the heavies. Bernie Campoli was in the Navy and he was one of the early guys. And Stan Waterman, of course.

EH: What was it like shooting Hollywood films?

Nicklin: That was always fun. Some of them were sort of crazy and some of them we were more proud of than others. Everything I did in Hollywood was with Al. Al and I had a good situation in that he wanted to be the producer, director, editor, seller…he wanted to be everything. All I wanted to be was a shooter. I wasn’t real competition to him. He’d do all the work, then call and say, “Chuck, your ticket’s in the mail.” I’d get on a plane and go somewhere in the world for a week or up to four months as a cinematographer, and when the film was over I’d get on a plane and go home. Al would spend the next two years editing and selling and promoting it. Al made more money; I had more fun.

Al is really aggressive in the business; he’s a hard worker. I was a little more independent than some of the others that worked for him, so I didn’t have to take some of the hard core rules that he would come up with. Often I was sort of the interface between the crew and Al. It always seemed to work.

Al and Stan Waterman and I worked together on The Deep. Al and Stan were the co-directors underwater; I was just an underwater cameraman. Peter Yates, the director, would say, “Al you get the long shot, Stan you get the eyes, and Chuck, get something good.” So I had a lot of time to go anywhere I wanted, shooting through holes and when the rushes came up I’d get a lot of comment because my shots were so different. One night we came back from the rushes, Yates and Peter Guber (producer) were standing in the lobby of the Southampton Princess Hotel when we got off the bus. They told Al and Stan to come right back down to talk about the shoot tomorrow. And I had a date with Jackie Bisset that night. Maybe there is something to just being a cameraman.

EH: Tell me more about The Deep.

Nicklin: We were in the Virgin Islands about a month. Peter Island was a great place. We had great parties: it was a really fun time. It wasn’t tough diving but we did a lot of dives. It was 80 feet to some parts of the Rhone, and when you make five dives a day like you do when you’re working with Al, we’d have an hour and half deco at the end of the day.

EH: Were you using tables?

Nicklin: We were using SOS meters, and just moved the needle up the letters for safety factors.

EH: Were any of the actors there on the Rhone dives?

Nicklin: Oh yeah. They slipped in there for their close-ups. And Jackie did more diving than she would have. She didn’t match up well with her double, didn’t like the way she looked on film, so she did more of the underwater thing than she would have as a rule. Waterman and Al were the co directors and the big shooters, and I was the third cameraman. When they were shooting Jackie in the t-shirt, I was just there with my mouth hanging open. She didn’t want to do it; she wasn’t happy with it. Peter Guber talked her into it. But she sure looked good.

EH: What were the actors like to work with?

Nicklin: (Nick) Nolte was crazy. He’d come in the morning just wiped out, he’d lay on a table somewhere half asleep, but when it came time to work, he worked. Jack McKenney was his double. A lot of things he did on his own too, because he wanted more in the film than just his face. In one scene when we had to swim through a cave to get to the jewelry, he had to hold his breath, and he did it. But that night he’d be off crazy somewhere and he’d come in and look like he’d been dragged behind a car. But when it came time to film, he worked.

(Robert) Shaw wasn’t around very much. He was friends with a lot of people in Bermuda. The last shot we had of him, where the eel came out, they’d kept him all day in his hut, and he was pissed. Kept drinking with one of his buddies while he waited, and he was pretty wiped. I remember him sitting there just chatting while Yates and Guber and Al were deciding whether it was safe to put him in the water. He turned to me and said, “Chuck, we really got to do this. I gotta have this closeup.” Al took him by the hand and tangled him up, and I took the camera. In the scene he really looks distressed and he is distressed. He did it in 5 minutes, we put him in the car and sent him home, and that’s the last we saw of him.

And Jackie was good. She didn’t like to be in the water and it was cold, but she’d get in and she’d smile and do what she had to do. She was really a neat lady. All three of them were all right. They’re movie stars. They just go in and have their pictures taken.

EH: What about the James Bond films?

Nicklin: The one I felt I accomplished the most on was For Your Eyes Only. We worked on that four months in the Bahamas. It was a nice film photographically. It was a bit hokey but most films are a bit hokey. What we did with the cameras underwater is something I can be proud of.

I’ve also done a bunch of funky little things where we did one or two scenes, falling into a pool or a raft. You get paid, it’s part of the job, but nobody ever hears about it.

Then there’s the time I spit in Sean Connery’s mask. We did Never Say Never, and there was a scene in a cave. Sean was only going to be in there for his closeup, but his mask wouldn’t clear. In that cave there was an air space where you could get out of the water. Al and I could communicate just by looking at each other. So he looked at me waved his hand, pointed at the mask, and signaled to get him out of here. We swam up so we could get our heads out of the water. I said, “Sean, I’m sorry but I’ve got to do this.” He said, “Whatever it is, I really need my closeup.” So I spit in his mask, put it back on his face, we went down, and got the shot.

EH: You worked on the Ocean Quest television series, which wasn’t very well received by the diving community. How come?

Nicklin: They thought it was going to be the Cousteau series. It wasn’t Cousteau; it was Hollywood. It could have been a lot better but it lost direction. Shawn Weatherly (Miss Universe) was a pretty lady, nice to work with, and she and I hit it off. I had time to spend with her without trying to hustle her. It was supposed to be this pretty girl having adventures, and it turned out to be this macho guy taking this pretty girl on a trip. And that’s what screwed it up. Al wanted to be the hero. It could have been really great, but it turned out to be a little more hokey because of the way it went.

EH: Was Al’s bends hit real or staged?

Nicklin: I think he had an embolism. We were diving side by side at 130 feet at San Clemente Island. We took decompression and all that. The difference was he jumped in a hot shower right after the dive. We called the Coast Guard and they were going to send a chopper, but the bubble passed and he was OK. A couple of hours later he was having dinner. But he was in big trouble for a while, and we were nervous.

What was staged was Shawn crying when she didn’t want to go back in the shark cage. She’d enjoyed watching the sharks. But the director told her to cry.

EH: How long was the shoot and where did you go?

Nicklin: Ten months all together. Antarctic, Truk, Cuba, Baja, and Newfoundland.

Lots of memorable things happened. The director had a big black zodiac with a big engine, and he shipped it all the way to Newfoundland. He was proud of it. It took the guys two days to make a trailer for it. We got it to the docks and he asked a fisherman, “Did you ever see anything like this?” He said, “Yeah, we have two or three of them in back.” He could have rented one.

Then we burned our hot air balloon. It caught fire in Truk. We took it all the way to Antarctica and never put it up.

Shawn was great and she didn’t get a very good deal out of it. It didn’t help her career because she wasn’t portrayed well in the film.

EH: Several of your protégés have gone on to bigger and better things.

Nicklin: The best is Howard Hall. I think he’s the best underwater photographer out there, period. For the kind of things Howard does, deep sea, 3d cameras and that stuff, he is the best.

He was an employee at Diving Locker, was very interested photography and diving. He was interested in sharks, and went with me on some of the early stuff with blue sharks when we still thought they’d bite. We were putting together the crew for The Deep to go to film the shark sequences in Australia. Al said we needed someone who isn’t afraid to shoot some fish and attract the sharks, and I said, “I know just the guy.” Howard hit it off really good with Stan Waterman. Stan took him under his wing, and got him on Wild Kingdom. He worked on that a long time and built his ability and reputation as a professional. My only part was that I got him out there where he might get bit by a shark.

Of course there’s Marty Snyderman, and he was working in the shop as an instructor. I’d come back from a trip with lots of stories and a little bit of money. And he said that’s what he wanted to do. I think they were all shooting with Nikonoses and the old Oceanic 35mm housing.

One of my favorite people who came out of the diving locker is my son, Flip. There’s some new guys too. Mark Thurlow worked for us in the Escondido store at one time. Lance Millbrand worked as my assistant on a couple of jobs with BBC, and he’s worked really hard getting into the business.

EH: When did you realize Flip had that drive and talent and was going to be so good?

Nicklin: I was doing a job for Sea World, shooting Panavision film in the shark tank, and Flip was shooting stills for them at that time. When he was in my way I’d be yelling and screaming and when I was in his way he’d be yelling and screaming. It got to the point when I said, “Goddam it this is my job,” and he said, “All right, now get out of the way.” That’s when I realized he’s serious, he’s going to be tough, and he wanted to be a photographer.

EH: How about your Imax films?

Nicklin: John Stoneman was the director of Nomads of the Deep. We did that with humpback whales and blue sharks, in Hawaii and in the Red Sea. There was a lot of competition as to who would have his hands on the Imax camera. Flip was the still photographer on that, and he shot his first humpback pictures in Hawaii, and that gave him a base for going back to National Geographic to eventually get an assignment. I did a couple of other Imax shoots as well, just doing scenes on location.

When we shot the stuff for Nomads of the Deep, the first pictures of the singers and all that, we used tanks and got away with it. But now they didn’t want you to use tanks because it would scare the whales. It would be a definite advantage to have a rebreather or a small tank.

EH: I’ve heard Flip say that it’s easier to shoot whales now than when he started.

Nicklin: It only makes sense. There’s generations of them, especially in Hawaii, their parents and grandparents are used to divers. They don’t have that fear of boats and motors they used to have when everybody they saw was trying to stick a harpoon in them. Flip says some of them hang out there, you could even lay on top of them if you wanted to. Flip says, free diving, he can lay right by the pectoral fin. Sometimes what you are looking for is an inquisitive calf that hangs around while the mother is just saying, “Come on kid, we’ve got to go.”

EH: Do you have any strong opinions on shark feeding?

Nicklin: If you don’t feed sharks there won’t be any. Look at the places where they feed sharks; they are protected. And where they don’t, they are fishing them for fins. It’s made people more aware and realistic about sharks and their behavior. I don’t see where it does any harm. Even at Cocos it seemed like the sharks were getting less and less until they started protecting them.

EH: Out of all your films, what stands out most in your mind?

Nicklin: I like the stuff we shot on For Your Eyes Only on the set, the sunken ancient city set. That was done in the ocean, not in a tank. They laid the tile floor and the whole thing. That was also when I blew up my condo. We all had condos up there in the Bahamas. One day I was sleeping on the side of the boat because I wasn’t needed till the next scene when someone woke me up and said, “You’re wanted on the radio.” The message was that your condo just blew up. We’d had a party the previous night and somebody left the propane on. When I left for the day and closed the condo up, the propane filled the room and a burner set it off. It blew out all the big glass doors.

EH: Speaking of sleeping, you have the reputation of being able to sleep anywhere.

Nicklin: My father always used to say, “Don’t stand when you can sit, don’t sit when you can lie down, don’t stay awake when you can sleep.” In the film business there is so much down time that you learn to take a break when you can, because you may be diving for the next three hours. I’ve always been lucky that if there’s a space I can wish my body in I can go to sleep. I’d crawl in on a shelf under the camera table which was covered with a blanket, and go to sleep. Whenever Peter Guber or any of the big guns showed up to start the day’s activities, a camera assistant would pound on the table and I’d crawl out.

One time I was diving with David Doubilet and Howard Rosenstein from Red Sea Divers out of Sharm el Sheikh. It was late, the boat was loaded with too much stuff, it was rough and looked like it might sink any minute. Howard said, “What are you doing?” I’d put all my stuff into my net bag and put on my BC, and laid down and went to sleep. There was nothing I could do; if we were going in the water I was ready.

EH: In all those years, you must have had some close calls.

Nicklin: The closest call, and I think the most dangerous diving I ever did was on the Doria. I was with Al and Jack McKenney. We were diving air; the deck is about 170, 180 feet. It was really dirty and cold, and if you miss the ascent line, you’d be in trouble because of deco and current. We got to the bottom and I was using the K100 (movie camera). It was a hand wind and the trouble was that if you wound it too far it would stick. We hit the deck and started off and I said, “My camera isn’t working.” They said, “See you later.” So I pounded on the camera and got it working, and filmed the ghost nets where lots of fish got trapped and died. I sort of kept track of where the ascent line was. Then Al and Jack showed up and we started up the line. Jack was right in front of me and all of a sudden kicked my mask off. So my mask is down around my throat, I’ve got a camera in one hand, a light in the other and I’m saying, “Oh, I’ve got to get this stuff together.” Putting the light under my arm getting the mask going…

Another thing that happened on one of those Doria dives is that Al and I were very competitive. On one of those dives he found a plaque that said “2nd class cabin” in three languages, and he thought that was hot. On the next dive I found the plaque that said “1st class cabin” in three languages. It was a plastic thing on a piece of wood, and I stuck it in inside my wetsuit. When we got to the deco stop I told Al, “Look at this,” and I reached inside my suit and pulled out just the wood. I’d lost all the stuff with the printing on it.

EH: How about close calls with animals?

Nicklin: I got nailed by that lionfish in Lembeh last year. I’ve never been bit, never been bent. In Vanuatu one time I rolled off the boat on to a silvertip, really spooked it. It came in on me and I had to beat it off with the camera. But considering all the things I’ve done and all the places I’ve been, the most pain I had was that lionfish a few months ago. But I only missed one dive.

EH: When did you make the transition to video?

Nicklin: I always wanted to do the next thing. I had one of the first video systems around here, an old JVC with a separate deck. The housing was a round thing that looked like a porcupine. Being new to video I though I’d do it all down there, shoot and edit. Well you don’t; you shoot it and edit later. It gave me a chance to shoot more on my own without a budget, because the price of tape was so much more reasonable than film. I’ve always been on the forefront of the people shooting video. Even now, as soon as they came out with high def that was in my price range, I jumped on it.

My idea of making a film is to do it on iMovie sort of like offline, hand it to Mary Lynn Price and have her clean it up. I’m not too excited about spending the rest of my life editing; I’d like to spend the rest of my life shooting. If I can get away with editing simply I’ll do it. When I get caught up. (laughs)

EH: Why did you start the San Diego Video club?

Nicklin: I felt that some of the still photographers hadn’t accepted the idea that video was here to stay. There wasn’t much support for video through the traditional photo groups. We were having meetings at the Diving Locker and I thought we ought to discuss video. It sort of outgrew that and we started picking up people who were interested in video. Mary Lynn really pushed for it and that sort of got it started. Then I started thinking we ought to have a way to share it. And that was the idea of UFEX (San Diego Undersea Film Exhibition), to share the stuff we worked so hard on, and give more people an opportunity to present stuff because all they needed was five minutes. (That’s the maximum time limit for each video.) The first one was at the San Diego Zoo’s auditorium, and that wasn’t quite big enough. And with the new theater at the Natural History Museum, it’s become a successful and very rewarding thing. It encourages a lot of people not only to do video but to have more respect for the ocean. Not only shares our chance to show what we’re doing but also shares how important the ocean is and how it should be protected.

I really reflect on the old shit I used as camera equipment. What I use now I can hold in the palm of my hand. I can carry it on the plane in my shoulder bag. With my old Arriflex and stuff, I used to fill four Igloos. It’s really great that not only has being a cinematographer become easier, but the quality is so much better. I’m shooting stuff that’s so sharp and so exciting that I can’t wait to go into the water. That’s why I’m going to New Guinea. I didn’t have anything going on and said, “I’ve got to go somewhere.” And when I take the stuff I shot with my high def camera and plug it into my high def video, I get so excited I can hardly stand it. I say, “Oh, I’ve got to do more of this.” I think that’s why I’ve always been in the forefront because I always wanted new challenges and wanted to make it better

EH: What do you see in the future of diving?

Nicklin: Pretty soon it’s going to be a travel business with a little diving. The tail is wagging the dog. They’ve got to make it fun and still make it exciting. There’s no excitement any more. We’re too careful. I think the best thing that’s happened is some of the shark feeds and stuff. Just to look at garibaldis isn’t enough. People want excitement, especially the kids.

Thank god there’s photography. Otherwise there wouldn’t be any growth in diving. Everybody’s got an underwater camera now. You don’t have to be big time any more. When the Nikonos came along, all of a sudden there was a push into photography. Now the same thing is happening with the digital point and shoots. Roz has this eight megapixel camera in a housing, and the whole thing is $400.

It’s not underwater photography any more: it’s photography underwater. Photography is bigger than the underwater. Does that make sense? It’s become more important than the diving.

EH: How does that translate into growth for diving?

Nicklin: Some of my travel customers are going back to stills. Its so easy to handle the stills compared to taking a piece of video tape and making it into something people want to see.

EH: Since the death of Jacques Cousteau, there doesn’t seem to be a figurehead for diving. Do you see anybody on the horizon?

Nicklin: Howard (Hall) could be great, but isn’t the kind of guy that wants to be. Someone could promote him and make him into the diving god. He looks good, he is good. But he isn’t interested. He’d rather fly his airplane.

EH: Do you dive locally any more?

Nicklin: I dove cold water for many many years and I used it all up. I don’t do any cold water diving any more. Been there and done that.

Unfortunately 9/10 of the US is cold. It’s not a good place to dive unless you get on an airplane and go someplace warm like Florida.

You’ve got to get people in the water without making them miserable. Instead of trying to get them to take another course, get them in the water and let them count fish.

EH: As you approach 80, what accommodations are you making for your age while diving?

Nicklin: One of the first things I do when I get on a dive boat is tell the crew, “You know, I’m getting sort of long in the tooth and I don’t carry all this heavy stuff, so I’ll swim to the back of the boat and hand up my gear. That’s the bad news. The good news is that I’m a big tipper.” That’s one of the things that’s important to understand. You’ve only got so much energy and you should use it most effectively. I use it most effectively when I’m in the water. I realize I’m not as agile as I once was, but in the water I’m as comfortable as I ever was. I might be a little more conservative as far as decompression. I’m aware age may have something to do with it and I don’t want to take the chance.

The youngsters sometimes look at us gray haired guys and wonder what we’re going to do. But then there’s a surface current and they are busting their neck and you’re hugging the bottom, passing them by and waving.

Seldom do I get excited in talking about the past. I’d rather talk about plans for the future. I’m much better at looking ahead. I’m going to be 80 real quick and I want to accomplish as much as I can while I still can.

And I can.